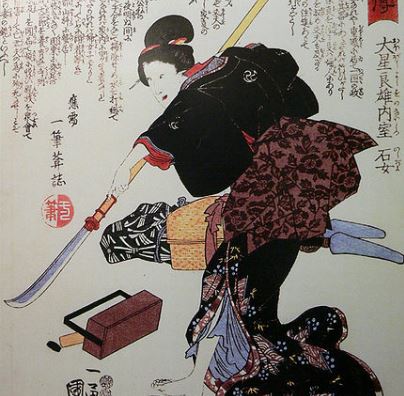

Deadly Life of a Female Ninja

/When we hear the word “ninja,” most of us picture those sword-wielding assassins wearing an all-black garb who are adept at martial arts and the art of stealth. We’ve read about these black-masked warriors in novels and comic books, and we’ve seen some fictionalized versions of them in a lot of movies for the past few decades. And in many of these materials, we’ve learned that a ninja is often a cloaked and masked man who can stealthily infiltrate an enemy’s territory to end the life of a specific target.

In reality, however, the way of the ninja is not a life solely intended for men, and not all ninjas live in the shadows. Yes, some of these ninja assassins were female, and they often hid in plain sight. These female ninjas were referred to as the “kunoichi,” and while they equaled their male counterparts in terms of combat and stealth skills, they handled their assignments differently from men in several impressive ways.

Defining Ninja, Shinobi, Kunoichi

While the term “ninja” is what became popular among Westerners, written records in feudal Japan refer to these covert agents and mercenary assassins as the “shinobi.” Members of the shinobi clans in Japan were practitioners of ninjutsu, which taught them the strategy and tactics of espionage, infiltration, sabotage, assassination and even guerrilla warfare. They were like the antithesis of the honorable samurai as the ninja’s covert methods of warfare were regarded as irregular and dishonorable. Nevertheless, as spies and assassins, many of the shinobi lost their lives while in the line of duty and usually took on missions from which they were not expected to return alive.

Medieval Japan was a time during which men dominated society while women were primarily relegated to the sidelines, taking “harmless” roles such as that of a wife, a mistress, or a maid. And so many incorrectly assume that ninja clans were strictly composed of males when the truth was women of that time also worked as covert agents and assassins alongside men although their approach in doing so is not the same as the male shinobi accomplished their missions.

The existence of female ninja warriors is mentioned in the Bansenshukai - a 17th-century book containing knowledge and secrets about ninja training. The Bansenshukai revealed the primary function of a kunoichi, and that is to infiltrate a target’s household by forming intimate relations with members of that clan and gaining their trust. Walking freely inside enemy territory and hiding in plain sight, they usually bided their time in collecting information about their target, but they were also capable of facilitating assassinations if ordered to do so.

Disguises And Tactics Of A Female Ninja

The shinobi knew the importance of using personal strengths to their deadliest advantage. In a world where women were prized for their beauty and were deemed ignorant and harmless, the kunoichi was less likely to arouse suspicion and found it much easier to get close to their targets compared to their male counterparts. The female ninjas used feminine wiles to accomplish their objective and even became concubines and mistresses to mask themselves for long periods of time.

The targets of the shinobi were typically powerful and influential members of the samurai class, which meant that they were heavily guarded and were naturally distrustful of men outside their clan. However, rarely were they as suspicious of the women around them as they were of men. This allowed the kunoichi to disguise themselves as maids, courtesans or as priestesses and go undercover, infiltrating dangerous enemy zones on a broader and more intimate level than male shinobis would have ever been able to achieve.

The kunoichi did not sneak in during moonless nights to steal information or eliminate their targets. A kunoichi was patient and took time to accomplish missions even if the mission took years. Female ninjas rarely attempted to kill their targets right away. First, they worked hard to integrate themselves well into the enemy’s household and to earn the trust of the household's many residents slowly. They gathered intelligence and passed on crucial information to a samurai’s enemies. When the time came to eliminate the target they were monitoring, they did not wait for a male shinobi to finish the job. Their combat skills were just as excellent, and sometimes, their method of execution was even more creative and brutal.

This is why some argue that the kunoichi posed a more serious threat than other members of the shinobi. It was hard to tell if a maid, a priestess or a courtesan was who she said she was since they could pretend to be one for a very long time if they must. And when they were ordered to strike, they did so cunningly when their targets are at their most vulnerable – often in bed and with their pants down. Hence, it is not so surprising that they suffered worse fates than the captured male ninjas when they were caught for committing such intimate betrayals.

Weapons Used By Female Assassins

Beauty and sexuality were the female ninjas’ primary weapons when gaining access to their targets, but they also wielded actual deadly weapons of their own. Considering they had to go to their enemy’s territory unnoticed, they could not bring around with them long swords that would catch people’s attention. Instead, they carried weapons such as dagger-like hairpins, throwing stars, tessen or folding fans with hidden blades, and poison as these items can be inconspicuous while wearing a standard kimono.

Perhaps the iconic weapon of choice used by the kunoichi was the neko-te. The neko-te mimicked Wolverine claws and was made of leather finger sheaths topped with very pointed metal tips. The tiger-like claws of the weapon extended between one and three inches in length and were sharp enough to tear away human flesh. Some of the kunoichis would even douse their neko-te with poison in order to quicken death or worsen pain.

Mochizuki Chiyome: Japan's Most Famous Kunoichi

There is little record available about kunoichis, and Mochizuki Chiyome is probably the only one whose name was solidified in Japan’s ninja history. Mochizuki Chiyome was a noblewoman from the 16th century and the wife of a samurai warlord. She is credited for setting up an underground network of female spies, which she accomplished by recruiting around 300 female orphans, war victims, and prostitutes.

To the eyes of the locals of Nazu village in the Shinshu region, the noblewoman was merely running an orphanage, but in reality, she trained and managed a very sophisticated group of female espionage operatives and assassins who have infiltrated almost every aspect of the region’s community. These groups of female ninjas put their bodies and lives on the line all in service to the Takeda clan led by the uncle of Chiyome’s late husband, Takeda Shingen.

For reasons unknown, after the death of Shingen in 1573, Chiyome and her league of spies disappeared from Japan’s historical records, and no one knows what happened to the secret group after serving the Takeda clan.

Although we don’t know all the names of the Japanese women who were once among the kunoichi, they were no less important than their male counterparts within the ranks of the shinobi. These deadly female ninjas were highly respected by the men they worked for and those who worked alongside them, and for a time, they were truly a force to be reckoned with in Medieval Japan.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kunoichi

http://www.ninjaencyclopedia.com/reality/kunoichi.html

https://www.criminalelement.com/blogs/2013/06/kunoichi-female-ninja-spies-medieval-japan-susan-spann

http://www.ancient-origins.net/history-famous-people/deadly-female-ninja-assassins-used-deception-and-disguise-strike-their-target-021503?nopaging=1

https://www.mysterytribune.com/kunoichi-closer-look-female-ninja-spies-old-japan/