10 Legendary and Mysterious Libraries of the Ancient World

/It is often said that knowledge is wealth and in the ancient world it is something that is well guarded more than gold or jewels. The colossal libraries ancient civilizations like the Greeks and the Egyptians built are testaments to the fact that all the riches of the world will always pale in comparison with knowledge and learning.

These days, when information comes to us lightning-quick at the touch of a button, we tend to underestimate and undervalue the privilege we have of unfettered access to almost anything that we want to know and learn. It is a little bit tragic that the sense of appreciation that we have for information and learning is eclipsed by our continuously shortening attention spans because of all the media we consume on a daily basis.

In today’s list, we take a step back thousands of years to days when information and knowledge are stored and jealously guarded in giant libraries that are often the first monuments to be destroyed and sacked in times of war or invasion. Libraries that have shaped the world we now know of and the civilizations that have walked the earth, each contributing to humanity’s progress.

So here are 10 legendary and mysterious libraries of the ancient world!

Number Ten: The House of Wisdom

Called by historians as the Cradle of Civilization, ancient Mesopotamia – now modern day Iraq – was once one of the world’s centers for learning. Alongside Greece, Egypt, and Rome, Mesopotamia had one of the largest institutions of learning built in the 9 AD at the heart of the city of Baghdad.

Known as The House of Wisdom, it was built during the reign of the Abbasids. The House of Wisdom’s “collections” revolved around literature from Persia, Greece, and India. Also, among the library’s collection are manuscripts on mathematics, philosophy, science, medicine, and astronomy.

The books alone were enough to serve as lures to scholars from neighboring regions in the Middle East and among them are the mathematician and one of the fathers of Algebra, al-Khawarizmi; and the philosopher al-Kindi.

The House of Wisdom was the epicentre of Islamic intellectualism and academia for hundreds of years until it was sacked by the Mongols in 1258, tossing many of its extremely valuable manuscripts and books into the Tigris. Legend even has it that the famed river turned black due to ink dissolving into its waters.

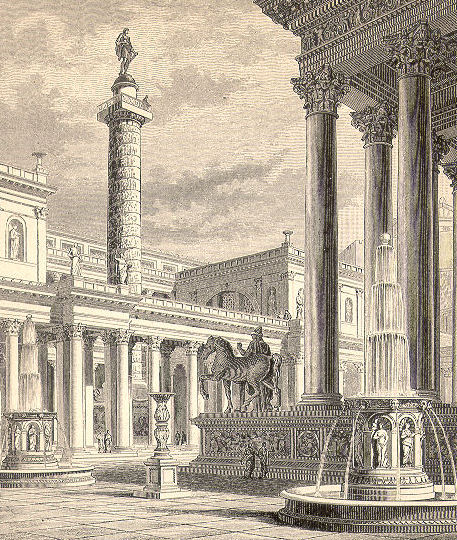

Number Nine: The Twin Libraries at Trajan’s Forum

The ancient Romans are no strangers to accumulating codices and scrolls filled with anything from mathematics to philosophy. Knowledge and information are cornerstones of their empire that lasted centuries.

A Roman emperor’s love of monuments has helped erect one – or two – of the ancient world’s largest libraries.

Around 112 AD Emperor Trajan completed the construction of a wide, multi-use complex at the heart of Rome. Within the bounds of this Forum are plazas, markets, and temples. However, its crown jewel is one of the Roman Empire’s famous libraries.

Split in two, the twin structures housed numerous works and texts in Latin and Greek – separately housed – and were built on opposite sides of Trajan’s column, a massive monument to celebrate the emperor’s military victories. Containing a collection of about 20,000 scrolls in rooms made of elegantly crafted marble and granite, historians are still debating when the twin libraries ceased to exist. With only texts referencing them until the fifth century AD, experts can only assume that it stood for at least three centuries.

Number Eight: Villa of the Papyri

One of the last ancient libraries to have survived well into the modern day, the Villa of the Papyri has withstood catastrophes including the devastating eruption of Mt Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Located in Herculaneum, Italy, the ruins of the Villa was buried deep in the ashes of Vesuvius that miraculously kept at least 1,785 of its scrolls preserved when the library was unearthed by archaeologists in 1752.

Technically the Villa was a house and not a library by any definition. Supposedly owned by Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesonius, Julius Caesar’s father-in-law, the massive home – aside from its impressive private library of texts on philosophy – boasted a collection of bronze sculptures and the most stylish and impressive architecture of that century.

Number Seven: The Library of Pergamum

Constructed by the Attalid Dynasty in the third century BC in what is now the country of Turkey, the Library of Pergamum was home to an impressive collection of 200,000 scrolls on varying subjects.

Located within a temple complex devoted to the Greek goddess Athena, the Library was considered to have become the “competition” of the Library of Alexandria according to the ancient chronicler, Pliny the Elder.

Apparently, both libraries sought to amass large collections of texts as well as establish rival schools of thought.

The rivalry between the two libraries allegedly reached fever pitch that Ptolemaic dynasty of Egypt halted the exportation of papyrus to Pergamum hoping that it would cripple the library. Unfortunately, things did not go according to plan and only turned the city of Pergamum as one of the leading producers of parchment paper.

Number Six: Nalanda University

Moving further south of Asia, the Nalanda University in Bahir, India, is considered to be oldest university in the entire world as the first European university only popped up in 1088, a whole six centuries later.

What is even more exceptional about Nalanda is that the university provided education to thousands of students all across Asia.

Its nine-storey library was nicknamed “Dharmaganja” or Treasury of Truth and “Dharma Gunj” or Mountain of Truth because it was highly praised for the largest collection of Buddhist texts among other writings and literature. Helping spread philosophy and the Buddhist faith, Nalanda has nurtured thousands of followers until it was destroyed by Turk invaders in 1193. Due to the university’s immense size, legend tells that it took the Turks months before they could completely reduce its foundations to rubble.

Number Five: The Theological Library of Caesarea Maritima

Before it was destroyed around 638 AD by invading Arabs, the Theological Library of Caesarea Maritima or simply the Library of Caesarea, had the largest collection of ecclesiastical and theological texts of the Ancient Christian and Jewish world.

As the center of Christian education and scholarship, the library was also home to a large collection of literature from Greece and other neighboring regions. Mostly the texts are primarily historical and philosophical but nonetheless valuable as the place was frequently visited by important historical personalities such as Basil the Great and Gregory of Nazareth.

The church father Origen was mainly responsible for the library’s inventory of 30,000 manuscripts but during the purge initiated by Emperor Diocletian, the library and many of its contents were destroyed. Afterwards, it was rebuilt by the bishops of Caesarea only to be completely torn down, brick by brick, by Arab invaders.

Unfortunately, not a single manuscript from the library’s collection survived.

Number Four: The Library of Aristotle

Built in the first century BC, the library of Aristotle was part of a larger structure called the Lyceum where he was sought by many of his students and spent time learning from one of history’s most influential philosophers.

300 years after Aristotle’s death, a geographer named Strabo chronicled one of the most detailed accounts of the philosopher’s magnificent collection in his Geographia XIII, 1, 54-55, saying that Aristotle was “the first man, so far as I know, to have collected books and to have taught the kings in Egypt hwo to arrage a library.”

Upon Aristotle’s death, the Lyceum was bequeathed to Theoprastus. Even before his death, Aristotle heard of the jealousy of the Attalid empire of his library and desired to covet it for the Library of Pergamum. When Aristotle died and the Lyceum passed on to a new owner, it was then decided that the library’s entire collection be hidden and kept safe underground.

Unfortunately, despite this noble effort, many of the books were damaged by moisture and the remainder of the collection were sold to a man named Apellicon of Teos.

Number Three: The Imperial Library of Constantinople

Most of the history of the Imperial Library of Constantinople is shrouded in mystery. Many would point out that it was built out of necessity to preserve texts that were already in danger because of deterioration.

It was in 357 AD when Byzantine Emperor Constantius II decided to build the imperial library where many of the deteriorating Judeo-Christian scriptures could be copied onto vellum, a material that lasts longer than papyrus. Although Constantius II was only mostly interested in religious texts, the Imperial Library still managed to salvage many other books and scrolls that housed the knowledge of the Greeks and Romans.

In fact, many of the surviving texts from the ancient Grecian world that survives today were copies from the original manuscripts of the Imperial Library of Constantinople.

Number Two: The Library of Alexandria

Built by Ptolemy I in 295 BC, the Great Library of Alexandria holds a prestigious title in history as a “Universal” library where scholars from all over the world would visit, share ideas, and study from over thousands of texts that it offers.

It was, in fact, the intellectual crown jewel of the ancient world. Texts and scriptures on subjects like history, law, science, and mathematics can be browsed among its collection of 500,000 scrolls.

Many visiting scholars that decided to remain and live in the library complex received stipends from the Egyptian government just for conducting their studies and copying texts. Among its visitors were Euclid and Archimedes.

Its demise is still a question that seeks answers. Supposedly, the library burned down in 48 BC when Julius Caesar set fire to Alexandria’s harbor when he was at war with Ptolemy XIII. However, many historians believe that a blaze could not have easily destroyed the library and it may have still survived for a few more centuries. Some scholars, on the other hand, argue that the library met its end during the reign of Roman emperor Aurelian in 270 AD while other experts place its obliteration somewhere around the Fourth Century AD.

Whatever the case and however it fell, the Library of Alexandria remains to be one of history’s greatest achievements both architecturally and academically.

Number One: The Library of Ashurbanipal

Known as the world’s oldest library, it was built and founded for the “royal contemplation” of the Assyrian ruler Ashurbanipal in the 7th Century. Basically, it was one massive private study.

Constructed in Nineveh in modern-day Iraq, the library had a collection of around 30,000 stone tablets written in cuneiform. What’s even more impressive is that the tablets were organized according to subject matter. Most of them being archival documents of the royal court, the collection also included a number of literary works including the 4000-year old Epic of Gilgamesh.

Ashurbanipal was a known book-lover and obtained many of them through looting from conquered territories including Babylonia.

Today, most of the surviving tablets are housed and cared for in the British Museum in London.

While the Library of Ashurbanipal may not be as glamorous as the Library of Alexandria, it is most interesting to note that his collection helped pave the way to the history of the written word through cuneiform.

Sources:

http://www.history.com/news/history-lists/8-impressive-ancient-libraries

http://www.onlinecollege.org/2011/05/30/11-most-impressive-libraries-from-the-ancient-world/

http://www.messagetoeagle.com/10-magnificent-ancient-libraries-filled-with-knowledge/

http://listverse.com/2016/12/09/10-mysterious-libraries/