The Ourang Medan, The Mystery of the Deadliest Ghost Ship in History

/In June 1947, the Dutch freighter S.S. Ourang Medan was traveling along the straits of Malacca, when the ship suddenly sent out a chilling distress signal.

"All Officers, including the Captain, are dead. Lying in chartroom and bridge. Possibly whole crew dead."

This first message was followed by a series of indecipherable Morse code sequences until finally, a last ominous transmission:

"I die."

Ourang Medan's grim SOS was picked up by British and Dutch listening posts around Sumatra and Malaysia, who worked together to determined where the signal was coming from and alerted nearby ships.

American merchant ship Silver Star was first to reach Ourang Medan. They waived and shouted at the vessel to check for signs of life above deck. But there was no answer. Only eerie silence.

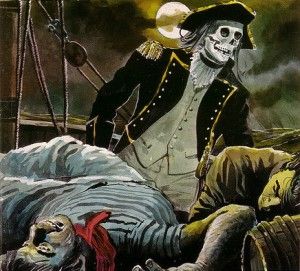

The US ship decided to send out a rescue team to board the ship to look for survivors. But what they found was a blood-curdling nightmare.

The entire Dutch crew was a ghastly pile of corpses – eyes wide open in horror, mouths are frozen in an eternal scream, arms stretched out as if saying stop as if saying no more.

Inside, they found the captain with the same twisted expression on his face as that of his men, dead on the bridge of the ship. Now nothing more than a dead captain, leading a dead ship.

His once strapping officers are now cold corpses straggled on the wheelhouse and chartroom floor. Even the ship’s dog wasn't spared a horrific death.

But the most harrowing is finding the radio operator, fingertips still on the telegraph where he sent his dying message.

After seeing the chilling devastation on board, the Silver Star decided to tow the Ourang Medan to port. But it wouldn't make it to shore, as thick clouds of smoke started rising from the lower decks and interrupted the rescue.

The crew barely had time to sever the line and move to safety, before the Ourang Medan exploded. The blast was apparently so big that the ship “lifted herself from the water and swiftly sank,” taking with it all the answers to its mysterious end to the bottom of the sea.

Or so the story of the Ourang Medan goes.

Some details may differ slightly in each version of the story. Like it happened in February 1948 instead of June 1947. Or that the waters that day were choppy instead of calm. And that the crew wasn't just dead, but they were decomposing at a faster rate.

While in some versions, the details are, well, too detailed. Like one of the two American ships that heard the distress signal was named The City of Baltimore. That the smoke from the lower deck before the explosion came exactly from the Number 4 hold. Or that the poor canine aboard was a small terrier.

But whichever version of the story you've heard (or told), the basic plot points remain the same - Ourang Medan's entire crew met a gruesome and inexplicable death, and then very conveniently blew up and sank to the bottom of the ocean, leaving us all with an unsolved nautical macabre mystery.

So what happened to the Ourang Medan?

Theory #1: It was a cover up.

The most commonly pointed out loophole in the tale of the Ourang Medan is the vessel's lack of paper trail.

The Lloyd's Shipping registers don't have any mention of the ship. It's not in The Dictionary of Disasters at Sea that covers the years 1824-1962. It wasn't in the Registrar of Shipping and Seamen either.

There's no trace of it in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. Nothing in the Dutch Shipping records in Amsterdam. The Maritime Authority of Singapore also doesn't have the ill-fated ship in any of their records.

In other words, the Ourang Medan was a ghost ship, even before it gained notoriety as one. Because there's no tangible proof that it even existed.

But as espousers of this legend would explain, it's because the Ourang Medan is part of a transnational government cover-up involving the Netherlands, Japan, Germany, China, the United States, and possibly many others.

They believe that the ship was deliberately expunged from all maritime records because it was being used to smuggle a secret cargo of lethal nerve gas to Japan.

Saying the Ourang Medan's voyage is linked to Army Unit 731 founded by Japanese bacteriologist Shirō Ishii, whose main objective was to bring back a weapon of the chemical, gas, or biological variety, that could win the war in their favor.

But as the Geneva Protocol of 1925 prohibited the use of all chemical and biological weapons in war, the only way a large shipment of poisonous gas could make it across the other side of the world without raising any suspicion from authorities is by loading it as inconspicuous cargo, in an old, beat up Dutch freighter.

This theory also provides a convenient and somewhat plausible explanation for the grisly death of the Ourang Medan's crew. With that much hazardous chemicals on board, a gas leak would've certainly led to the immediate death of everyone in the ship.

However, it wouldn't explain why the rescue crew from Silver Star wasn't affected by the poisonous gas when they boarded the ship.

Or why, like the Ourang Medan, there’s no mention of the Silver Star in Lloyd's register.

Theory #2: It was carbon monoxide poisoning.

American author and inventor of the term Bermuda Triangle, Vincent Gaddis, speculates that it was carbon monoxide poisoning is the answer to the mysterious deaths of the Ourang Medan crew.

According to his theory, burning fuel from a malfunctioning boiler system produced carbon monoxide fumes that poisoned the crew.

When breathed in carbon monoxide enters the bloodstream and prevents red blood cells from carrying oxygen around the body. At high levels, carbon monoxide can cause dizziness, vomiting, seizures, loss of consciousness, and even death.

The trouble with this theory is that Ourang Medan is not an enclosed space. Fumes could've simply escaped into the atmosphere, and lives of the crew working the upper decks of the ship would've been spared.

Theory #3: It was pirates.

What's a story about a ghost ship without pirates, right?

There are theories claiming that pirates invaded the Ourang Medan and killed everyone on board, which although doesn't explain some accounts saying that there were no visible wounds on the victims' bodies, it does fit with the Strait of Malacca's long history with piracy as far back as the 14th century.

Because of its geography - narrow and dotted with many islets - it makes it ideal for a surprise attack towards ships using it as the trade route to China and Europe.

Theory #4: Ghosts

One of the most repeated, but arguably, also the most inconsequential detail in the story of the Ourang Medan is the extreme chill the rescue team felt as soon as they entered the hull of the ship, despite it being 110°F outside.

Inexplicable drop in temperature plus the frightened expressions on the crew's faces set in a vast, unforgiving sea, equals ghosts did it.

There aren't many supporters of this theory, but what's a ghost ship story without a ghosts-did-it theory?

Theory #5: Aliens

You might think that the alien theory is the most far-fetched, the most uncreative, the most cop out theory explaining the phenomena of the Ourang Medan, but it's a very popular theory, with entire books dedicated to it.

The story of the Ourang Medan has all the elements of a good mystery - inexplicable deaths, unknown assailants, world powers, war, pirates, ghosts, and multiple highly-plausible conspiracy theories.

Which is probably why it still fascinates us to this day, even if it's already been dismissed by historians, researchers, and the casual internet fact-checker alike as a hoax.

But if it's good enough for the CIA to release a document in 1959 saying, that the Ourang Medan holds the key to many of the sea's mysteries, including that of sightings of huge fiery spheres that come from the sky and descend into the sea, then, it's certainly a hoax worth retelling.

Sources:

1. Death Ship: The Ourang Medan Mystery, http://mysteriousuniverse.org/2011/11/death-ship-the-ourang-medan-mystery/

2. The Myth of the Ourang Medan Ghost Ship, 1940, http://skittishlibrary.co.uk/the-myth-of-the-ourang-medan-ghost-ship-1940/

3. S.S. Ourang Medan, http://www.crime-mystery.info/great-mysteries/ss_ourang_medan/the_hoax

4.S.S. Ourang Medan, https://www.historicmysteries.com/ourang-medan/

5. CARGO OF DEATH, https://web.archive.org/web/20070205223141/http://www.neswa.org.au/Library/Articles/A%20cargo%20of%20death.htm

6. LETTER TO<Sanitized> FROM C.H. MARCK, https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP80R01731R000300010043-5.pdf

7. Did the Ourang Medan “ghost ship” exist?, https://skeptics.stackexchange.com/questions/20263/did-the-ourang-medan-ghost-ship-exist

8. The SS Ourang Medan: Death Ship (Updated), https://shortoncontent.wordpress.com/2015/01/15/the-ss-ourang-medan-death-ship-updated/

9. Mysterious Death at Sea: the Disturbing Discovery at the S.S. Ourang Medan, http://weekinweird.com/2011/07/17/mysterious-death-sea-disturbing-discovery-s-s-ourang-medan/

10. The Mammoth Book of Unexplained Phenomena: From bizarre biology to inexplicable astronomy, https://books.google.com.ph/books?id=YHCeBAAAQBAJ&lpg=PT263&dq=Vincent%20Gaddis%20ourang%20medan&pg=PT263#v=onepage&q=Vincent%20Gaddis%20ourang%20medan&f=false

11. Vincent Gaddis, http://self.gutenberg.org/articles/eng/Vincent_Gaddis

12. Crime on the high seas: The World's Most Dangerous Waters, http://www.cnbc.com/2014/09/15/worlds-most-pirated-waters.html

13. The World's Most Dangerous Waters, http://time.com/piracy-southeast-asia-malacca-strait/