Who Are The Mysterious Sea People?

/In the region of the eastern Mediterranean between the 13th and 12th century BCE, records of ancient history spoke of a powerful confederacy of naval warriors known as the “Sea People.” According to one ancient inscription, this band of sea-faring raiders “came from the sea in their war ships” and that they were such a force to be reckon with that “none could stand against them.”

They launched attacks against several ancient civilizations that resided in the Mediterranean and wreaked havoc on nations and empires like Egypt, the Hittite Empire, Syria, Palestine, and Turkey. But despite their legendary place in human history for supposedly being a fierce force that contributed to the catastrophic collapse of several Aegean and eastern Mediterranean civilizations during the Late Bronze Age, not much is known about who these Sea People really were and where they actually came from.

Scholars and experts have presented several theories about the potential origins of the mysterious Sea People, but there’s hardly a consensus on which is the better theory that answers the enigmatic identity of these ancient maritime warriors. This is why the extensive discussion over their main homeland and nationality continues to spark controversy to this day.

Ancient Records About the Sea People

Most of the limited information that historians and experts have about the Sea People came from the ancient civilizations that fought against this mysterious naval confederacy once or in several occasions. The ancient Egyptians, in particular, were in conflict with them on many instances. In fact, three of the great pharaohs of Egypt – such as Ramesses II, Merenptah and Ramesses III – recorded their encounters with the Sea People. Not only did these Egyptian leaders boasted in their inscriptions about their victories against their formidable adversaries, they also provided the most detailed narratives referring to this mysterious civilization of sea-faring raiders.

Ramesses II’s Inscription

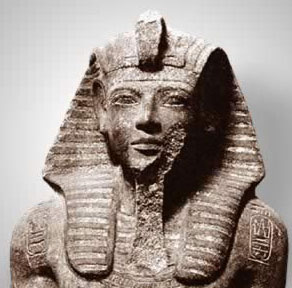

The existence of the Sea People was first revealed and described in the middle of the 19th century by a man named Emmanuel de Rougé, who served as the Louvre’s curator at the time. His interpretations about the Sea People came from the famous Medinet Habu inscriptions, which is considered as the main source as well as the basis of various discussions about the sea-faring confederacy in the Mediterranean region. But it has been agreed on by various experts that the earliest possible record of the Sea People is traced all the way back to the reign of Ramesses II, the third pharaoh of the 19th Egyptian Dynasty.

Early in the reign of Ramesses the Great, the Egyptians came into conflict with the Hittites when, in 1274 BCE, the latter seized the trade site of Kadesh - which is now located in modern-day Syria. Ramesses utilized his army and attempted to expel the Hittites - an effort which he claimed resulted to a great victory for the Egyptians although this is disputed by the account of the Hittites.

But regardless of whether or not Ramesses II defeated the Hittites during this clash, what really makes his inscription so valuable is what the pharaoh said about the Sea People. Based on his account, the Sea People were the allies of the Hittites who were also mercenaries that served under his own forces. He also mentioned how he thwarted the naval attack of the Sea People by sinking their war ships and how after their defeat, many of them joined Ramesses’ army and even became a part of his elite group of guards. However, the pharaoh made no mention of their nationality or where they came from, and experts suggest that this implies that the Sea People required no introduction to those who would have heard the pharaoh’s story as the citizens of that time probably already knew a lot about them.

Merenptah’s Inscription

It was Ramesses II’s successor Merenptah who encountered the Sea People again during the fifth year of his reign in 1209 BCE. During Merenptah’s rule, the Egyptians battled against the Libyans when they tried to invade the Nile Delta. The pharaoh wrote about the conflict and mentioned in his writings that the Libyans brought allies during their invasion and they were naval forces that came “from the seas to the north.” He listed their territories which included Teresh, Ekwesh, Sherden, Lukka and Shekelesh.

While many scholars have tried to figure out where these lands were located in terms of the modern world we live in today, they did not achieve much success in answering this mystery. What is known for certain is that Merenptah was particularly proud of his feat of suppressing these sea-faring adversaries that he made sure that tale of his army’s triumph was immortalized in his inscriptions which were found on the walls of the Temple of Karnak as well as on the famed Merenptah Stele from his funerary temple at Thebes.

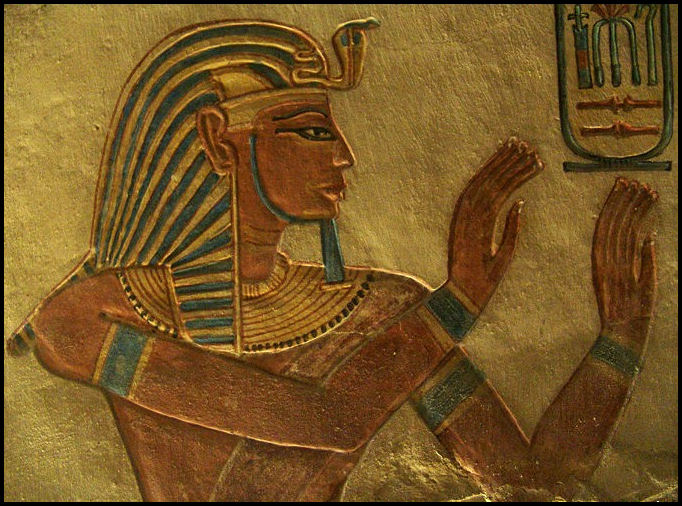

Ramesses III’s Inscription

Despite Merenptah’s success in securing the Egyptian borders from the members of the Sea People who were trying to establish permanent settlements in the country, the naval confederacy returned once again to mount another invasion during the reign of Ramesses III, the second pharaoh of Egypt’s 20th Dynasty. The Sea People allied themselves once again with the Libyans, and this time, they launched an attack at the trading center in Kadesh and raided establishments along the coast. They also attempted to occupy and take control of the Delta but failed to do so when Ramesses III’s forces managed to thwart their efforts in 1180 BCE.

In his victory inscription, Ramesses III listed several countries that united to form the maritime confederation, and they included the Peleset, Shekelesh, Tjeker, Weshesh and Denen. It is believed that Peleset occupied approximately the same region as today’s Palestine, and that Tjeker is located somewhere in Syria. Ramesses III also noted in his inscription that the Sea People were confident in “coming forward toward Egypt” as they had already brought the Hittite state to its knees in 1200 BCE.

In order to defend Egypt from the occupation of the naval confederacy and the Libyans, Ramesses III formed a strategy that avoided engaging the Sea People in the battlefield. Instead, he resorted to guerilla tactics and utilized archers to shower the enemy’s war ships with flaming arrows. This led to the destruction and sinking of the invaders’ vessels. The remaining forces of the Sea People that managed to reach land were also defeated, and the battle to protect Egypt officially concluded with the fall of enemy forces in the city of Xois in 1178 BCE.

Members of the Sea People suffered from various fates. Some died from the conflict while those who survived were either imprisoned, sold as slaves, or forced to join Egypt’s army and were subsequently assimilated into Egyptian culture.

Speculations About the Identity of the Sea People

For almost a century, the Sea People were probably the most feared naval warriors in the Mediterranean region around three thousand years ago. But for some reason, they eventually vanished from the face of the earth, leaving very few traces behind. Historical evidence we have today are only enough for us to be aware that they once existed, but do not give us much to go on in determining where they came from and what happened to them after their several invasion attempts that tested the might of Egypt.

As for who they really were, there are probably dozens of theories and hypotheses presented by scholars that claim to answer this mystery. Some have suggested that the Sea People could be related to the Philistines, the Etruscans or the Trojans, the Minoans as well as the Mycenaeans.

There is even a speculation that the enigmatic Sea People could be connected to the little-known Luwian civilization of that time, a coalition of kingdoms believed to have brought the downfall of powerful ancient civilizations by the end of the Bronze Age in the Mediterranean region. Not only did the Luwians supposedly destroy the Hittite Empire, they also weakened and destabilized the Egyptians. It purportedly took the Mycenaeans to band together and form a coalition of their own to successfully topple the Luwians and destroy their key cities, which included Troy. However, as the last civilization standing, the Mycenaeans eventually fought amongst themselves, and their civil war led to the total collapse of the Mediterranean area.

There are just too many blanks for us to fill before we could accurately determine the real identity and origin of the enigmatic Sea People who once raided the Mediterranean region in ancient times. Perhaps the day will come that we will finally get to answer the most basic questions of who they were and were they came from, but for now, it looks like this is one of those many mysteries in this world that may never be resolved within our lifetime.

Some historians even say that there is no longer a necessity for mankind to passionately pursue the uncovering of the identity of the Sea People since it’s a venture than can never come into fruition. Nevertheless, as curious creatures of Earth, we just can’t help ourselves. We are drawn to all things mysterious, and the enigma of the ancient Sea People is one mind-boggling puzzle that modern man will always dare to solve.

SOURCES:

1.http://www.history.com/news/ask-history/who-were-the-sea-peoples

2.http://www.ancient.eu/Sea_Peoples/

3.https://www.newscientist.com/article/2087924-world-war-zero-brought-down-mystery-civilisation-of-sea-people/

4.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sea_Peoples

5.http://listverse.com/2016/06/06/10-theories-regarding-the-sea-peoples/